Risk Assessment or Business Impact Analysis: What Comes First?

What Comes First? RA or BIA

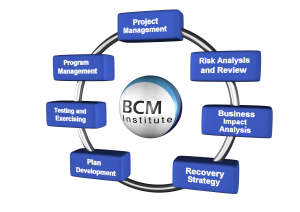

Over the past few years, I have been asked this question and also noticed the many discussions among professionals on the topic of whether one should, when going through the BCM planning methodology, conduct Risk Assessment (RA) or Business Impact Analysis (BIA) first. Often, these discussions are long and go on with the hasty conclusion in sight. They are rife with inconsistencies, misconceptions, and opposing viewpoints that have resulted not necessarily from any error on the professional’s part, but from the conflicting national Business Continuity Management (BCM) standard, each practitioner subscribes to. I would like to shed some light on some of these inconsistencies and misconceptions, as well as offer my thoughts on the RA versus BIA discussion itself.

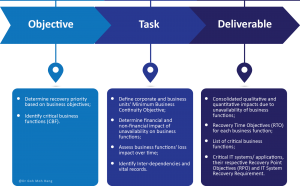

The Risk Assessment and Business Impact Analysis are fundamental components in ensuring the development of an effective BCM framework in an organisation. However, there has been much confusion about the difference between the two phases, and that should come first have been a long debated topic. To be able to determine the exemplary process, we must first understand the objectives and expected deliverables of each phase.

Getting definitions out of the way

I’ll like to start by saying that Risk Assessment (RA) and Business Impact Analysis (BIA) are not the same things. They have gradually been used more and more interchangeably as similar processes, and this is not only incorrect but not identifying the individual features in each process can prove detrimental to your organization’s business continuity. The detailed definition can be found in BCMPedia.

Risk Assessment

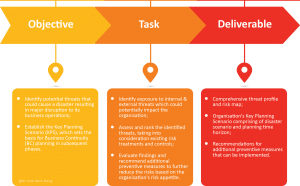

Risk Assessment (RA) is the process of identifying internal and external threats and vulnerabilities, identifying the likelihood and impact of an event arising from such threats or vulnerabilities, defining the controls in place or necessary to reduce exposure and evaluating the cost for such controls.

Risk Assessment (RA) is the process of identifying internal and external threats and vulnerabilities, identifying the likelihood and impact of an event arising from such threats or vulnerabilities, defining the controls in place or necessary to reduce exposure and evaluating the cost for such controls.

Risk Assessment is a phase within the BCM planning process. It is the overall process of risk identification, risk analysis and risk evaluation. It is NOT to be confused or conflated with risk management, which is similar but separately defined as the identification, assessment, and prioritization of risks, followed by coordinated and economical application of resources to minimize, monitor, and control the probability and impact of unfortunate events. The primary objective of Risk assessment is to lessen vulnerability and decrease risk.

Business Impact Analysis

Business Impact Analysis (BIA) is the process of analysing the effect of interruptions to business operations or processes on all business functions. The scope of Business Impact Analysis includes facilities, It Infrastructure, Hardware, and Data. The main objective of Business Impact Analysis is to identify the operational and financial impacts resulting from the major disruption of business functions and processes, and thus, BIA is incredibly crucial to Business Continuity Planning. The outputs from RA are a bit different from those of BIA.

RA gives you a list of risks together with their values, whereas BIA gives you timing within which you need to recover (Recovery Time Objectives or RTO) and how much information you can afford to lose (Recovery Point Objectives or RPO). So, although these twos are related because they have to focus on the organization’s assets and processes, they are used in different contexts.

What does ISO22301 BCMS standard say?

The International Standard ISO 22301:2012 allows for both approaches, depending on the BCM planning methodology that is used. Organisations may choose to conduct BIA to identify their critical business functions followed by RA to analyse and mitigate the potential risks faced by each business operations and processes. The advantage of this approach is that it focuses on the identification and mitigation of specific business threats faced by each business unit. Another approach would be to conduct RA to identify threats and establish the risk landscape at the corporate level before conducting BIA. As the BCM framework is set up to prepare and build resiliency against corporate-wide disruptions, it is reasonable to assess threats and estimate the possible period of disruption at the corporate level. The outcome could be used to establish the Key Planning Scenario, which sets the basis for planning in the subsequent stages.

An effective Business Continuity Management framework ensures the capability of an organisation to continue delivery of products and services at an acceptable predefined minimum level and safeguard the interests of key stakeholders. The understanding of potential threats faced by the organisation and the determination of recovery priorities set the foundation for BCM implementation. Our preferred approach would be first to conduct an RA at the corporate level to establish the Key Planning Scenario, which could be used as a benchmark for determining the organisation’s critical business function in the BIA. To mitigate the RA not completed correctly, in ISO22301, a continuous review using RA is repeated in the BIA and then the BC Strategy phase.

What do the other standards say?

- Australia (HB221:2004): “Risk & Vulnerability Assessment” is step #2, whereas “Conduct BIA” is step #3

- Canada (Z1600-08): Risk Assessment precedes BIA as part of a continuity project planning activities

- Great Britain (BS25999-1:2006): BIA precedes the Risk Assessment

- U.S. (NFPA1600 2007): The Risk Assessment takes precedence, with the BIA being a subset of the RA

- Singapore Standard (SS540:2010): Risk Assessment precedes BIA as part of a continuity project planning activities

As you can see, every standard offers a different take or variant on what comes first, and some of these standards do not factor in Risk Assessment. Additionally, business impact analysis is mandatory for ISO 22301 implementation, but not for ISO 27001. Who, then, do we subscribe to for a universal take on what is right?

Why Risk Analysis first?

Some practitioners and most of the older international BCM standards believe that the RA should come first as it enables one first to identify exposure and risks, allowing the practitioner to develop the necessary mitigation measures to reduce the threat. It also allows the practitioner to perform BIA more quickly as the lists of assets in the organization have been completely identified.

Most of the international standards support this claim, with RA being regarded as the initial step to take before the BIA.

Additionally, will have a better impression of which incidents can happen which risks you are exposed to. Therefore, be better prepared for doing the business impact analysis that focuses on consequences of those incidents. Furthermore, if you choose the asset-based approach for risk assessment, you will have an easier time identifying all the resources later on in the business impact analysis.

Why BIA first?

The counter argument against using RA first is that in sufficiently large organizations, it can be quite difficult, if not flat out impossible, to access all the risks and their impact on the organization. Rather than going for RA first, it would be much easier to go for BIA first, evaluating all the critical functions (or prioritised activities as ISO22301) and assets of the business and how they will impact the organization.

Different business units or departments in large organizations often have their individual subcultures and approaches to work. By showcasing a complete list of risks to critical business functions that have been identified from all parts of the business, new thinking and debate almost always ensue. Thus, some would argue that employing BIA first saves everyone involved in the BCM process an enormous amount of time and effort.

Different business units or departments in large organizations often have their individual subcultures and approaches to work. By showcasing a complete list of risks to critical business functions that have been identified from all parts of the business, new thinking and debate almost always ensue. Thus, some would argue that employing BIA first saves everyone involved in the BCM process an enormous amount of time and effort.

BIA forces the practitioner to consider which assets are of most importance to your business and its continuation. RA will then be applied afterwards to access the potential risks against these critical functions, followed by forming a mitigation plan to counteract the risks involved.

Sometimes, practitioners start with BIA because they want the organisation to talk about business processes and assets. This is often a strategy, and it should not be part of this discussion.

Conclusion

Conclusion

It is a matter of preference and circumstance. It can be conducted before, after, or even concurrently with one another, depending on what the situation demands. Some implementers felt that the combined effort to gather the information combined with one interview was time saving. As a practitioner, the argument is what constitute RA – it may require you to conduct a field RA survey.

When RA and BIA are placed together, these two processes combined can easily tell how hard a potential disruption can impact a business, as well as how quickly and how damaging it can be.

It is always good to have a healthy discussion but the key message does we have the same understanding of the RA and BIA definitions, are you speaking when you are just starting a new BCM project or updating an existing program, do you have other standards already in place such as ISO9000, ISO27000, and consulting techniques to gain acceptance of organisation.

It is always good to have a healthy discussion but the key message does we have the same understanding of the RA and BIA definitions, are you speaking when you are just starting a new BCM project or updating an existing program, do you have other standards already in place such as ISO9000, ISO27000, and consulting techniques to gain acceptance of organisation.

I would expect comments, and there are strong opinions on both sides with justifications. However, having spent some time in this industry, I would like to take a middle ground that there is no true right or wrong position on this debate as it is from which perspectives you are starting from and essentially what meets the requirement of the internal or external customers’ needs.

About the Author

Dr Goh Moh Heng is the President of BCM Institute and the Managing Director of GMH Continuity Architects – a specialized BCM Consulting firm. His primary areas of expertise include Business Continuity Management (BCM), Disaster Recovery Planning (DRP), ISO22301 BCM Audit and Crisis Management. Since 2011, Moh Heng has assisted more than 20 organizations, particularly those operating in the Asia Pacific and Middle-East Region in their successful implementation of their Business Continuity Management System (BCMS) and achieving their BS 25999/ SS 540 / ISO 22301 organization certification. Before establishing BCM Institute and GMH BCM Consulting, Dr Goh held senior positions with some large organizations. During his career with the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation (GIC), he was responsible for all aspects of its BC and contingency planning. At Standard Chartered Bank, he saw to the global implementation of its BC management and planning. He also managed the BCM practice at PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Currently, Dr Goh is the senior advisor to the China BCM Forum, a quasi-government agency responsible for BCM throughout China and an expert panel member of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Network on Improving SME Disaster Resilience (since 2011) and JICA-ASEAN study to enhance resiliency of industrial areas against natural disasters (since 2012). He hold a Ph.D. and also been awarded the highest level of certification from the three major business continuity management institutes. He is the author of nine business continuity management books. Dr. Goh is instrumental in creating the first Wikipedia for BC www.BCMpedia.org. He can be contacted at moh_heng@bcm-institute.org or moh_heng@gmhasia.com.

References

Goh, M. H. (2016). Risk Assessment or Business Impact Analysis: What Comes First? LinkedIn Pulse

Goh, M. H. (2015). Business Continuity Management Planning Methodology. International Journal of Disaster Recovery and Business Continuity, 6, 9–16. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.14257/ijdrbc.2015.6.02

Kosutic, D. (2014). Risk assessment vs. business impact analysis. Advisera, (Mar), 2–5.

Ross, S. (2010). A business impact analysis checklist: 10 common BIA mistakes. Search Disaster Recovery, (Oct).

Rupert, J. (2013). The Relationship Between the Business Impact Analysis and Risk Assessment. Avalution Perspective.

Zecuboy. (2013). Risk Assessment versus Business Impact Analysis. Information Security Cafe, 5–8.