Business continuity management implementation for small and medium-sized enterprise

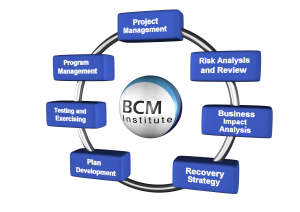

In this article Dr. Goh Moh Heng and Jeremy Wong look at some of the difficulties that SMEs face when it comes to making business continuity plans and how a simplified methodology could make things easier.

Article was published at Continuity Central on 3 July 2015

Introduction

Business continuity has risen in focus in Asia and elsewhere over the last few years and this is especially true for companies operating in regulated industries. The recent series of mega disasters in the Asia region has resulted in larger organizations investing heavily in improving their resilience against disruptions to business operations. However, despite the growing awareness of business continuity, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) do not appear to be taking action to enhance their business resiliency.

Business continuity is still not widely understood in small and medium-sized enterprises. Many relate it to emergency response or IT disaster recovery and even those that have heard of business continuity may see no relevance to themselves.

Unlike many large firms that have business continuity plans in place, SMEs often lack the time and the money to invest in their business continuity plans. But increasing pressure from larger organizations to secure the continuity of their supply chains, new government legislation, and the global acceptance and adoption of business continuity management standards, mean that SMEs can no longer ignore business continuity and the growing need for it as part of mainstream business operations.

Working assumptions for SMEs

SMEs are often associated with the following characteristics when it comes to business continuity:

- They have an entrepreneurial culture;

- They have limited resources for ‘non‐productive’ investments;

- They have limited or no knowledge of business continuity;

- They are not in a position to develop a business continuity plan to the fullest extent;

- They have some IT‐knowledge, but usually not about systems availability and IT recovery.

Obstacles to implementation by SMEs

Lack of understanding of business continuity management

One of the main obstacles to successful business continuity plan implementation in SMEs is a lack of understanding of the importance of business continuity, the development processes involved and the maintenance activities that are needed to sustain the programme. Many owners and managers vaguely acknowledge business continuity management’s place in large corporate organizations but see little relevance in their small businesses. This lack of understanding inevitably leads to misconceptions about the importance of BCM:

- Underestimating the impact. SMEs owners tend to make the assumption that the business can survive financially and that customers will accept lack of service during a period of disruption.

- Scenario assumptions. There is an assumption that the many potential scenarios are either too small to require action, or are too large, and therefore are beyond their planning capability.

- Time and manpower resource affordability. There is a constant assumption that SMEs cannot afford the cost or management time to make business continuity plans.

- Living within the comfort zone. Many SMEs assume that the majority of disruptions can be managed when they happen, with no need for pre-planning.

- No sense of urgency. There is a lack of prioritization of business continuity because the SME has never experienced a crisis and therefore does not understand the priority that should be given to BCM.

BCM professionals do not share the message outside large corporations

Full-time BCM professionals focus exclusively on developing plans for their organizations and do little advocacy work with SMEs.

Making the process too complicated

Proponents of BCM often over-compensate for the lack of advocacy by overwhelming listeners with shovel loads of information, without regard to how much of the information can be understood. There are very few presenters who can present business continuity content in a very simple and concise way.

Providing a step-by-step process

The key for SMEs is to provide them with a simple and easy to implement approach. This is often overshadowed by a complicated methodology that requires a team of specialists to implement. The unnecessary expectation that a perfect business continuity is required is a daunting starting position for SMEs.

Too expensive to implement

For many SMEs, having a business continuity plan is often seen as an expensive luxury.

BCM has a higher return on investment for SMEs

The truth of the matter is that for SMEs, the development of business continuity plans is far more valuable, and simpler, than most think. Conversely, SMEs have more to lose should they be caught without a business continuity plan in a disaster. While large corporates may have resilience arising from the diversity and spread of income sources, and operational work locations, smaller organizations more often than not have none of these advantages. For most SMEs, the exposure is far greater due to an inherent and almost inevitable concentration of critical risk factors. Due to a simpler structure, plans developed for SMEs are also often more straightforward and easily implementable.

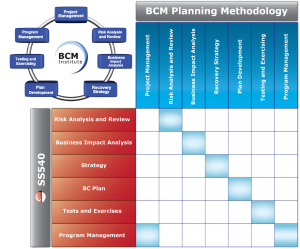

SMEs need a new methodology

It is clear that although SMEs desperately need business continuity planning, the traditional methodology for developing them does not work. It is too time-consuming, labour intensive and costly. BCM practice should be a solution rather than problem focused. As solutions for global corporates come with a hefty price tag, the more modestly priced solutions adopted by SMEs hold less interest for the business continuity and disaster recovery vendors, who continue to push for more sophisticated (and correspondingly higher priced) products; hence the myth that business continuity is too costly for the smaller organization. It simply is not attractive for many disaster recovery vendors to bother promoting their services to smaller organizations.

The starting point for a BCM framework for SMEs

Three questions need to be examined when first embarking on a business continuity planning project. They centre on:

- Purpose: Why is your company introducing BCM?

- Scope: Which parts of your business will introduce BCM?

- Team: Who will lead and manage your BCM activities?

The answers to these questions will help frame the project and provide a grounded perspective that will drive management and project team members in a direction that will yield the most benefit to the organization.

Leadership in a business continuity project is crucial for success. Business continuity planning projects typically involve participants from across the organization. Without a strong mandate from management, many of these projects fade away after a brief period of activity, being superseded by ‘more pressing concerns’. Leadership can also be demonstrated by way of a policy emphasizing the importance of business continuity to the organization, the purpose, scope and assumptions, an organizational framework and structure for the implementation and subsequent management of the BCM programme.

Start with the survival scenario

One way SMEs can accelerate the development of a business continuity plan is by focusing on the essentials. An SME with limited resources should look at mitigating its risks and containing any damage to as low a level as possible such that it would be able to resume operations at an acceptable level of functionality in a relatively short period. This is a company’s survival scenario. BCM is all about a company’s ability to achieve its survival scenario.

Here are some warm-up questions to get SMEs started:

- Q1: What disaster scenarios might lead to bankruptcy of the company?

- Q2: How quickly (in hours, days or weeks) does your company have to recover to ensure that it will survive a disaster-related disruption?

- Q3: What are the critical resources whose availability determines the life or death of your company?

- Q4: Within five to ten years, what kinds of disasters and accidents are most likely to impact you, potentially triggering a worst-case scenario?

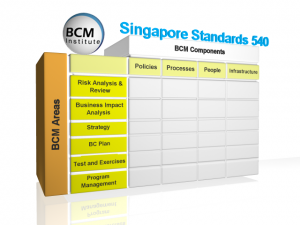

Aligned to international standards?

There is much scepticism about whether or not international standards for BCM, such as ISO 22301, can be applied to the SME marketplace. The answer to that lies in understanding why the standards exist in the first place. Many people misinterpret international standards to mean methodology. This is not the case. What standards do is to ensure that any business continuity plan produced will be based on a sensible evaluation of risk; a business understanding of consequences should key processes be lost; and a suitable strategy to mitigate damage and ensure recovery.

The ISO 22301 standard has been available since 2012. SMEs are beginning to feel the pressure from major clients to adopt and comply with this standard. Many compare its adoption with that for the ISO 9001, whereby SMEs are excluded from bidding for large contracts if they do not meet the ISO quality standard. Procurement contracts are beginning to include business continuity readiness by the suppliers as part of the terms and conditions. SMEs that implement ISO 22301 can improve their resilience in the same way as larger organizations. A smaller company may have tighter budgets and resources to put the necessary BCM processes and business risk management in place but by focusing only on the essentials, an SME can remove the unnecessary expense and complexity of implementing ISO 22301.

Manage emergencies and incidents

Before SMEs begin working on a business continuity plan they should first check that basic emergency procedures are in place, including:

- Make sure that your employees understand emergency evacuation procedures;

- Make certain that your employees know what to do if a fire breaks out;

- Ensure your employees know what to do if a colleague is injured.

These are all part of essential occupational health and safety legislation and are a legal requirement for any businesses. It is imperative that all businesses have and follow basic emergency procedures to ensure safety at all times.

Define disasters and assess risks

It is vital to recognize that a disaster could happen to any organization – no matter the business size. Before looking at the risks in individual areas of the business, it is important to determine what would constitute a disaster. In simple terms, a disaster is an incident that has serious consequences for the company.

Frequent small business disasters include:

- Fire/flooding.

- Computer/telecoms failure.

- Key equipment failure.

- People issues such as illness/resignations/maternity leave.

- Denial of access to the premises.

- Product defects.

- Bomb/terrorism threat.

- Legal/regulatory action.

- Utilities failure.

It is critical that SMEs understand the disruptions that would be disastrous to the running of their business when writing the business continuity plan. Take the time to identify all the risks your business faces and then rank them in order of likelihood and importance.

Once the risks have been identified, for any risk you can:

- Transfer it via insurance.

- Reduce it by less centralization and more resilience.

- Eliminate it by changing procedures.

- Accept it if the impact is relatively small.

- Manage it.

Adequately assessing the disasters that could threaten your company will give you a fair idea of the business areas that are most critical to achieve. Usually, these will be the areas on which your business relies the most, and which are exposed to the greatest degree of risk. This is the most important part of your plan. The following checkpoints are essential when writing this stage of your plan. It is important to go systematically through each of the following areas and take a practical approach to tackling each of the threats that your business may face. Follow the same process for each:

- Identify threats and resources.

- Assign ownership.

- Develop business continuity plans and policies.

Premises and key equipment

Clearly, premises are vital to any SME. So much so that SMEs often take them for granted. However, SMEs need to consider the long-term impact that damage to, or destruction of, premises would have on the business. The same applies to business-critical machinery. If a necessary piece of equipment is destroyed, damaged or stolen, what impact would it have on the business? Ask the following questions:

- Would you be able to notify your workers and clients of disruption to the business?

- What would happen to customer orders during the time that the premises were closed?

- Would you be able to make alternative arrangements for regular orders, to keep loyal customers happy?

Test the plan

Once the business continuity plan has been agreed and endorsed by management, it should be communicated to your teams, preferably through a formal walkthrough session whereby team members are invited to comment. This will test the feasibility of the plan and expose any flaws. It will also ensure that key roles and responsibilities are understood. At some point in time, it might be worth conducting a physical simulation of the business continuity plan to ensure its smooth running should the plan need to be executed.

Regularly update the plan

Review the plan at least every six months. Monitor to see that contact details for the recovery site, suppliers and the team are up-to-date and correct. Similarly, review whether there have been changes in the organizational structure, or in a team’s functions, and update if necessary. Distribute the plan to staff involved in the execution of the plan and advise them to keep copies off-site. Team meetings are useful forums to remind all employees of the processes to follow.

Help for SMEs

Undoubtedly, SMEs need help if they are to implement BCM with any measure of success. The following suggestions could be considered to inch these companies towards greater resilience progressively:

- Create more awareness programs amongst SMEs. Greater education about the importance of planning for a major disruption that could potentially cripple their business would certainly help.

- Offer assistance for SMEs to build BCM capability, either by sending key staff for relevant training on managing a BCM programme, or by engaging an external consultant to advise and guide the organization towards mitigating its risk and putting in place response and recovery mechanisms.

- Establish and enforce industry guidelines and regulations to require companies to implement BCM.

- Provide incentives to companies to achieve industry standards.

Conclusion

Achieving ISO 22301 BCMS certification in itself is not the solution. Over-emphasis on certification may well lead to a tick-box audit mentality that leaves the typical SME with additional costs of compliance without any of the real advantages of a proper BCM. A well-rounded programme, incorporating a healthy dose of education mixed with incentives, regulation and enforcement, is necessary to bring about the real benefits of BCM to SMEs.

The authors understand the difficulties that a busy manager in a typical SME faces when it comes to implementing business continuity. Hopefully this article will make his or her job a little more enjoyable and easier to undertake successfully. If not, at least, he or she will know they are not alone.

The authors

Dr Goh Moh Heng, BCCLA BCCE CMCE CCCE DRCE, is the president of the BCM Institute and the managing director of GMH Continuity Architects – a specialized BCM

Dr Goh Moh Heng, BCCLA BCCE CMCE CCCE DRCE, is the president of the BCM Institute and the managing director of GMH Continuity Architects – a specialized BCM

consulting firm. Dr Goh has assisted organizations, particularly those operating in the Asia Pacific and Middle East Region in the successful implementation of their business continuity management system (BCMS) and achieving their BS 25999/ SS 540 / ISO 22301 organizational certification.

Jeremy Wong BCCLA BCCE CMCE DRCE is the senior vice president of the BCM Institute. He is also the senior vice president for GMH Continuity Architects and is a senior management staff member responsible for all training and consulting initiatives.

http://www.bcm-institute.org/

References

APEC SMEWG. (2013). Guidebook on SME Business Continuity Planning. BCP Guidebook.

BSI Group. (2013). ISO 22301 for small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs). BSI. Retrieved from ISO 22301 for small and medium-sized businesses (SMEs)

ENISA. (2010). IT Business Continuity Management An approach to Small Medium Sized Organization. ENISA: BCM: An Approach for SMEs, 127.

European Commission. (2014). What is an SME? European Commission Enterprise and Industry. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/enterprise/policies/sme/facts-figures-analysis/sme-definition/

ISO 22301. (2012). ISO22301:2012 Societal Security – Business Continuity Management Systems – Requirements. Societal Security – Business Continuity Management Systems – Requirements (1st ed.). Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

Marinos, L. (2010). Strengthening the weakest link: Business Continuity Management for SMEs. ENISA, (Oct).

Maruya, H. (2008). BCP in Japan: Diffusion and Expectation. The concept of Business Continuity, 1–4.

Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, J. (2006). Guidelines on Formulating and Implementing BCPs for Small and Medium Enterprises. Preparations to Ensure the Business Can Survive Any Emergency Situation, 1–117. Retrieved fromhttp://www.chusho.meti.go.jp/keiei/antei/download/110728JapanBCP_SME_Eng.pdf

Price, R. (2005). The personal side of Business Continuity. Continuity Forum, 1–2.

Wiltshire County Council. (2006). Business continuity guide for small businesses. Business Continuity Guide for Small Business, 1–19.